Qingqi (qing-tsi, qing qi, qing tsi), or celadon is a type of porcelain, perfect for Chinese traditional tea drinking collectible tea.

The word “tsintsi” can be translated as “blue-green pottery”. In the West, such dishes are more often called celadon (according to one version, this name comes from the name of the shepherd from Honoré d’Urfe’s novel Astrea, who wore light green clothes).

Some historians believe that Qingzi ware began to be made more than two thousand years ago. Other researchers believe that production began in the 10th century. It is known for sure that in the Southern Song Dynasty (IX-XII centuries), there were already kilns for firing in the Lun Quan area in what is now Zhejiang Province.

Qingzi ware quickly gained popularity both in China and abroad. European aristocrats and royalty spent large sums of money to buy this porcelain. Augustus II, the ruler of Saxony, even built a palace to store qingzi wares. The Portuguese wrote in their trade reports that “celadon wares are the most beautiful of all that men have invented, more beautiful than gold, silver or crystal”.

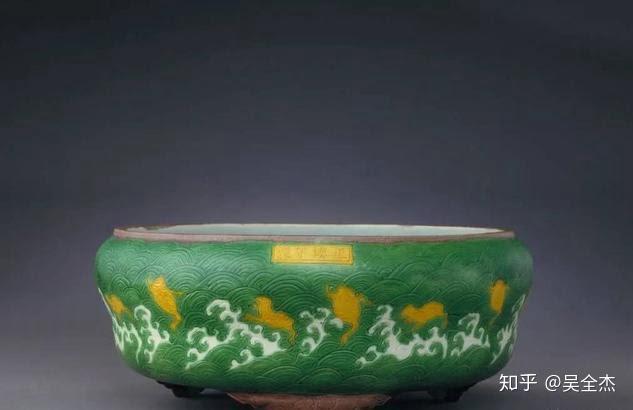

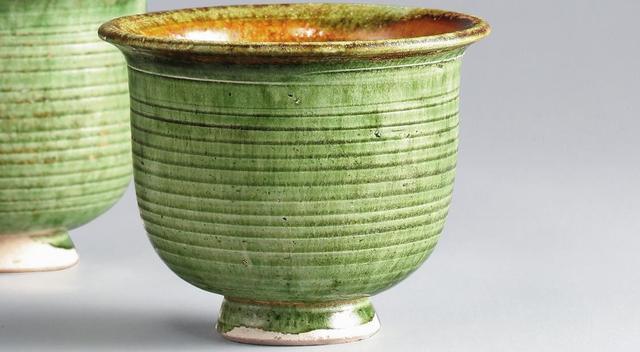

In the production of cinci is used high-temperature firing (more than 1000 degrees) and a special glaze with the addition of iron oxide, because of which the dishes acquire a greenish-blue color and a special luster. Zinci products are very dense, with thick walls, rounded and smooth. Such ware is sometimes compared to jade.

Glaze color ranges from light green or pale blue (the color of lake water) to greenish (the color of green plum), dark green or grayish blue (the color of a stormy sky).

In production often used a special technique, which causes the surface appear small cracks – the so-called crackle, which give the products a special color, a patina of antiquity, the color of antiquity.

Most often, dishes made of zinci are not decorated with anything, so as not to distract attention from the beauty of the lines and the beautiful color of the glaze. Sometimes masters add small decorations, for example, at the bottom of the cup make a relief in the form of a small fish or flower. Vases are decorated with a modest ornament that emphasizes the exquisite shimmer of the glaze.

Zinci ware is good for making tea, celadon ware is slow to heat up and slow to cool down. The cup holds heat for a long time, and the tea is beautifully set off by the deep color of the glaze. Some tea treatises wrote that qingzi is best for drinking green tea, as the color of the glaze blends beautifully with the color of the tea infusion. Celadon ware is good for other types of tea as well.

Ceramics (tao 陶) is the oldest and most extensive branch of Chinese arts and crafts.

In Chinese tradition, the invention of pottery is attributed to legendary ancient rulers – the Divine Farmer (Shen-nung 神農 ), the Yellow Emperor (Huang-di 黃帝). Such legends are set forth, in particular, in the early chapters of Zhu Yan 朱琰’s (18th century) treatise Tao sho 陶說 (Word on Porcelain), published in 1767.

In addition to pottery itself, ceramic materials were also widely used in the fine arts for the production of funerary and temple sculpture and relief compositions, as well as architectural details and many other categories of objects. However, the following discussion will focus exclusively on tableware.

Typology of ceramic ware.

Chinese ceramics are formed by many different regional varieties, which are subdivided into three main types in recent specialized literature:

- “pottery products”,

- “stone” ceramics

- porcelain.

The term “pot tery products” (or “pottery goods”, in European terminology “earthware”) unites products made of ordinary clays and fired at temperatures between 800-1000º.

“Stoneware” ceramics (“stoneware”) and porcelain are products made from ceramic masses containing kaolin (kaolin clay, gaolin-tu 高嶺土). This is the name given to the fraction of liquid and refractory clay that has the substance kaolinite in its composition, formed during geological processes from aluminum and silica-containing rocks. Its complete chemical formula is: Al20 2Si02 2H20. The term is derived from the toponym Gaolin 高陵 (High Hills), the name of the area and hilly ridge stretching from north to south at the junction of Henan and Hebei provinces. Deposits of kaolinite-bearing clays are also present in many other geographical areas of China. They run in a wide belt across its northwestern and central regions, under the thickness of loess soils, and then emerge closer to the surface along the spurs of mountain ranges in the territory of Hebei and Henan provinces. The richest and best kaolinite-bearing clays are concentrated in the southeastern and southern regions of China. All European terms used for porcelain are unrelated to its original name.

The term “porcelain” comes from the Persian word bagpur, which, in turn, is considered a distorted transcription of the title of the Chinese emperor – tian-tzu 天子 (Son of Heaven) and means “imperial”, i.e. it records the highest public authority of porcelain products. Italian and French terms (respectively porcelana and porcelain) go back to the Latin word porcella – “white shell”, and figuratively betray the color of the shards of these products. The English name of porcelain – Chayna, which came into use in Europe in the XVI century, also comes from the Persian word chini, which in the countries of the Arab-Muslim region was customary to name China.

In Chinese, all ceramic varieties containing kaolin, including porcelain, are designated by the word – qi 瓷. Therefore, not so long ago and in European art criticism there was no clear differentiation between porcelain and “stone” ceramics: objects belonging to it were qualified as “proto-porcelain”, “porcelain-like” or products “with porcelain-like shards”.

Differences between porcelain and “stone” ceramics

Porcelain and “stone” ceramics are fundamentally different in terms of the composition of the ceramic dough and the peculiarities of the technological process. An obligatory component of porcelain mass is “porcelain” stone (tsi-shi 瓷石) – a rock of volcanic origin, which is a compound of feldspar and white mica. The manufacture of “stone” pottery involved the addition of quartz-containing substances, as which sand was most often used. “Porcelain” stone, if used in it, then in different proportions than in porcelain. The process of making “stone” ceramics did not require such a thorough cleaning of components, as porcelain production, so the ceramic shard usually has a greenish, pale cream or grayish-white color, noticeably different from the snow-white shard of high-quality porcelain (porcelain of low quality is sometimes characterized by minor color impurities).

The next fundamental difference between “stone” ceramics and porcelain lies in their firing temperature. The firing temperature of “stone” ceramic varieties, depending on the time and geography of their manufacture, ranges from 1050 to 1250º. The firing temperature of porcelain should not be less than 1350º, only then there is a qualitative transformation of the original physical structure of the ceramic mass, and it, thanks to the silicon contained in kaolin clay, becomes vitreous, translucent and completely waterproof.

History of the development of Chinese ceramics

The initial stage in the history of the development of Chinese ceramics belongs to the Neolithic era, when the basic technological methods of pottery making, the basic set of categories and forms of products and ways of their ornamentation were formed…

Ceramics of the Tang 唐 (618-906) era. The main events of Chinese pottery of the Tang era are considered to be the further development of the previous varieties of “stone” ceramics, the expansion of the geography of ceramic centers, accompanied by the appearance of new varieties and the invention of porcelain. The written sources describing this era name six major ceramic centers:

- Yuezhou-yao 越州窯,

- Dingzhou-yao 鼎州窯,

- Wuzhou-yao 婺州窯,

- Yuezhou-yao 岳州窯,

- Shouzhou-yao 壽州窯

- Hongzhou-yao 洪州窯.

The latest archaeological findings have lengthened this list to 18 pottery centers. The main place in the hierarchy of ceramic varieties was occupied by a new variant of “green pottery”, called yue-tsi 越瓷, “yue pottery”, after the Yuezhou 越州 region (in the right bank area of Hangzhou Bay, eastern part of the present-day Zhejiang Province). Zhejiang). Known as Yuezhou-yao, “Yuezhou workshops/kilns,” this ceramic center actually united many small workshops (the territories of present-day Shaoxing and Shaoxing counties). Shaoxingxian 紹興縣, Xiaoshanxian 蕭山縣, Shangyuxian上虞縣 and Yuyaoxian 餘姚縣).Spread over an area of more than 70 square kilometers, they were concentrated around Shanglihu上林湖 Lake, which served as their main source of water. “Yue pottery” differed from its predecessor qingqi varieties produced in the same area in the 3rd to 6th centuries in several essential features:

Firstly, the greater care in cleaning the components of the ceramic dough, as a result of which the shards of the products acquired a stable grayish-white color, although the firing temperature remained within the same limits and even slightly decreased (to 1190-1200º).

Secondly, by complicating the glaze recipe by introducing new mineral additives, including titanium and copper oxide, which provided the glaze coating with rich yellow-green and green colors. Thanks to them, ceramic items became externally similar to jade objects.

In addition to “sweat” glaze, which served as the main decorative element, vessels were decorated with relief images of dragons and birds, and sometimes decorated and short hieroglyphic inscriptions indicating the purpose of things, for example, “cup for tea”, “cup for bitter tea”. It is possible that Yuezhou-yao workshops were a state production center working for the needs of the court (so-called secret furnaces, bise-yao 秘色窯). Archaeological confirmation of the conjecture that “Yue ceramics” belonged to luxury items, used as feast and liturgical utensils, was the discovery of a set of 16 items received by the hierarchs of the monastery as a gift from members of the Tang imperial family in 1987 on the territory of the Famensi monastery 法門寺 (northwest of the modern city of Xi’an, Shaanxi Province).

A precursor to the famous celadons, ceramics produced in the Lunquan 龍泉 workshops, Yue ceramics served as a model for many other Tang period productions.

In the southeast of the country, the largest center for the production of imitations of yue-tsu was the Wuzhou-yao workshops, which also united many kilns located in the central part of Zhejiang Province (present-day Jinhuaxiang 金華縣 counties). Zhejiang (modern counties of Jinhuaxian 金華縣, Lanxixian 蘭溪縣, Dongyangxian 東陽縣, Yongkangxian 永康縣, etc.).

These kilns worked on local varieties of kaolin, referred to as red soils, and, along with imitations of Yue ceramics, produced specific dishes with a decorative coating of dark red and dark gray glaze. Several large regional centers also functioned in the middle reaches of the Yangtze.

Along with the already mentioned Hongzhou-yao workshops, these are:

Shouzhou-yao 壽州窯 and Xiao-yao 蕭窯, located in Anhui Province. Anhui Province (in its center, near modern Huangan 淮南, and in the northern end, Xiaoxian 蕭縣 County, respectively), they were famous for tea ware with glaze of yellow, green and (less often) white colors;

Yuezhou-yao 岳州窯 (modern Xiangyinxian County 湘陰縣, northern Hunan Province) is a place of production of green, yellow, brown and green-brown glazed wares.

Among the “northern” centers that most reflected the influence of the tradition of monochrome glazed ceramics are the Yaozhou 耀州 workshops in the central part of modern Shaanxi Province (90 km north of Xi’an). By 1984, the remains of more than 40 workshops, 50 kilns and an impressive number of products dating to the Tang, Five Dynasties (Wu-dai 五代, 907-960) and Northern Song (Bei Song 北宋, 960-1127) eras had been discovered here.

It has been suggested that these were the workshops called under Tang Dingzhou-yao and were the site of the original production of dark glazed ceramics.

Three-color watered pottery” (san tao 三彩陶)

However, in general, the most popular pottery in the middle reaches of the Huang He is the varieties covered with polychrome glazes and made mainly from ordinary clays. The best known is “tricolor watered pottery” (santsai-tao 三彩陶) or “pottery with multicolored/polychrome glazes” (tsaiseyu-tao 彩色釉陶).In modern art history, this type of ceramics is unanimously considered one of the highest achievements of the entire decorative and applied art of the Tang era, which embodied the most important aesthetic attitudes of the time and the influence of foreign (in this case, Persian) artistic traditions on Chinese art.

Until the middle of the last century, “tricolor watered pottery” remained known only in literary descriptions and stylizations made already in the XV-XVII centuries. Its first authentic samples were found in 1949 in one of the burials in the vicinity of Luoyang (Henan Province).

Today it is established that this variety began to produce in the last quarter of VII century, and the heyday of its production fell on the first half of the VIII century, when in the technique of san-tsai in addition to tableware and various vessels performed a large number of samples of small funerary plastic, smokers and headboards.

The main center of production of “three-colored watered ceramics” were opened in 1957 workshops Gongxian-yao 鞏縣窯 (modern county Gongxian, near Luoyang).Pottery san-tsai was distinguished by the complexity of the technological process, allowing several variants. The composition of the glaze included lead, oxides of copper, cobalt, iron and manganese, enriching the glaze coating with a rich palette of green, yellow and brown colors and shades. Many items were fired at a temperature of 1170-1300º. In this case, the glaze, abundantly applied to the surface of the objects, “flowed”, forming irregular, partially overlapping multicolored flows, which could be supplemented with paintings.

And in another technological variant, the products, previously covered with white engobe, were fired at a temperature of about 900º, glazed and subjected to a second firing at a temperature of about 800º. Additional glazes could also be used in decoration, most often made on the basis of cobalt, the rarest and most expensive coloring agent at the time, as well as coloring of individual fragments of the product (for example, the rim of a plate).

The production of “three-colored irrigated pottery” continued, gradually declining, into the Northern Song period, until it finally ceased. This may have been due to the destruction of san-tsai production centers as a result of the partial conquest of China by the Churchens, but it is also likely that the colorfulness of such ceramics came into conflict with the new aesthetic criteria established in Chinese art of the 10th-13th centuries.

Currently, the PRC has revived the production of products similar to the Tang “tricolor watered pottery”, if not in technological, then in aesthetic terms. Existing as a regional art craft, this production mainly solves the problem of creating souvenir products imitating funerary sculpture of the Tang era. Most often, tourist-oriented statuettes of horses and camels, which are stylizations of the most popular examples of funerary plastics of the VII-VIII centuries, as well as large-sized figures, which are in demand among the local population as decorative garden sculptures, are made in this technique.

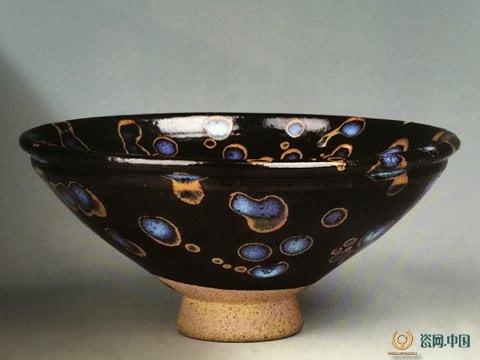

Ceramics with colored glaze – huayu tao 花釉陶

Along with the “three-color glaze pottery” in a number of workshops in the middle reaches of the Huang He – Lushan-yao 魯山窯, Jiaxian-yao 郟縣窯 (modern Henan province), Jiaocheng-yao 交城窯 (Shanxi province) and Tongchuan-yao 銅窯 (Shaanxi province). Tongchuan-yao 銅窯 (Shanxi Province) and Tongchuan-yao 銅窯 (Shaanxi Province) produced a peculiar in technological terms ceramics, decorated with two-color glaze flows – huayu-tao 花釉陶, “ceramics with colored glaze”.In its decorative finishing, a coating of black, yellowish-brown or olive-green was applied to the vessel body, over which glaze of other colors – blue, bluish, gray – was sprinkled.

During the firing process at temperatures above 1000º, the glaze of the main tone fused with glaze splashes, forming a spectacular decoration in the form of contrasting spots and flows (e.g. gray-blue with black flecks on a black background).

The tradition of painted ceramics continued in the Tang period, largely due to the work of workshops Tsizhou-yao, which then produced mainly the so-called popular ceramics (min-tao 民陶) – products of mass demand, intended for ordinary people.

Much more remarkable is the fact of the emergence of a center of painted ceramics in the southern regions of China, where monochrome ceramics had previously prevailed. Such a center were the workshops of Tongguan-yao 銅官窯 (or, Changsha-yao 長沙窯), located in the central part of the modern province of Hunan (27 km northwest of Changsha). Hunan (27 km northwest of Changsha). They became known thanks to archaeological work (1979), which revealed the remains of 19 kilns and numerous finished products.

It turned out that this ceramic center emerged in the middle of the Tang Dynasty, reached its peak by the 10th century and ceased to exist in the same century. According to the unanimous opinion of experts, Tunguan workshops represented not only a large-scale production, but also an independent art school that used polychrome painting with copper-based paints for finishing ceramics. Green and red colors in combination with brownish-yellow and brown glaze prevailed in the painting.

Researchers distinguish five types of paintings: first, geometric patterns consisting of rhombuses, circles, cross-shaped figures, which can be supplemented with stylized images of clouds, waves and lotuses. Secondly, compositions on the theme of “flowers and grasses”, usually including images of water lily flowers, the distinctive feature of which is a combination of broad strokes and thin strokes, sometimes supplemented with light undercolor, which brings these compositions closer to easel painting. Thirdly, zoomorphic subjects, usually executed in an expressive manner, with a few vigorous strokes, including images of real representatives of the animal world – animals, birds and fish, and fantastic creatures (dragon, phoenix). Fourth, landscapes remotely resembling landscape painting on scrolls. Fifth, genre compositions, among which scenes of children playing and depictions of officials are noteworthy.

In the decoration of ceramics, inscriptions were actively introduced, sometimes replacing pictorial scenes. Although the products of the Tangguan workshops were obviously not in mass demand on the domestic market, they constitute an important link in the history of the development not only of ceramics but also of Chinese porcelain.

During the Tang, Five Dynasties and Northern Song eras, porcelain evolved from a regional product common in northeastern China into the main type of Chinese ceramics. However, different varieties of “stone” ceramics continue to exist in parallel with it, and some of them play a role in the arts and crafts of modern China.

(from the book “Spiritual Culture of China”, encyclopedia in 5 vol. / ed. by M.L. Titarenko; Institute of the Far East. – M.: Vost. lit., 2006-. Т. 6 (additional). Art / ed. M.L. Titarenko et al. – 2010. – 1031 с. С. 246-261; Author: Kravtsova M.E.)